Trusted Messengers: Year 2 Learnings of Community Health Worker Pilot in Suburban Cook County

Community Health Workers and their supervisors from Health & Medicine’s Pilot in the Western Suburbs meet pre-pandemic to share lessons learned in one of their bi-monthly learning collaborative meetings.

Read the Community Health Worker Pilot Year 2 Outcomes Report here!

As the pilot program continues into its third year, Health & Medicine Policy Research Group (program coordinator) and Sinai Urban Health Institute (lead evaluator) recently released the pilot’s Year 2 Outcomes report. The report summarizes the learnings and outcomes of the pilot during a significant and challenging 2020.

Last year, Jocelyn Moreno, a community health worker (CHW) from Mujeres Latinas en Acción, walked one of her clients from Summit, Illinois, through a financial assistance application over the phone. Her client, an older man who recently lost his job and was the sole wage earner in his household, had encountered language and technology barriers in this application process, as he has had with other applications, and needed Jocelyn’s help. Because it was challenging to provide instructions over the phone, she referred him to her supervisor who could assist him with a new application that had just opened with the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights. This type of financial assistance was also hard to come by in the suburbs, particularly for undocumented immigrants. Later on in the conversation, she learned that he also needed access to food and so she connected him to different food pantries available in his neighborhood.

He is one of the many individuals Jocelyn has helped since even before the pandemic hit. Because of this close relationship, she recently heard from him regarding the COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccine access and distribution in the western suburbs have been sporadic compared to in Chicago. At the time, she was able to get him and his wife registered in the city, but they faced barriers to taking advantage of those appointments.

“He was like, ‘I finally found a gig after so long. I’m backed up in bills and rent. I can’t take it’, said Ms. Moreno, “It’s understandable. It’s like, ‘Do you want to pay your bills today? Or, do you want to get vaccinated?’ That’s the harsh reality for a lot of our clients”.

Since access to transportation was also an issue for him, he needed to find a site closer to home, including one that had Spanish speakers and flexible dates and times. With the help from her contact at Summit Park, she found out about an upcoming vaccination event held in Summit and registered him and his wife for it.

Because of Jocelyn’s long-term relationship with her client, he knows he can reach out to her and Mujeres Latinas en Acción for help, and she can also anticipate future needs.

“I stay in contact with my clients even if they don’t have needs at that time,” says Ms. Moreno. “But I always ask, ‘Are you working? Is it consistent? How many hours?’. They’ll reply and say, “It’s only for two, three months. It’s not enough.’ I already know that after those three months, they’ll need some assistance again. So I take note of everything so I can be prepared for when they need help.”

—

This story is one of many that the community health workers in the CHW pilot program, a joint funding effort by Community Memorial Foundation and Healthy Communities Foundation, have encountered since it began in 2018. They have been a lifeline for the numerous individuals they have helped navigate the confusing and, at times, inaccessible system of health and social services and resources over the past year.

The two foundations funded the pilot to improve the quality and cultural competency of service delivery in the western suburbs of Chicago. In a short period of time, Jocelyn and her fellow CHWs in the pilot transitioned from explaining what a CHW was to working with 70+ clients each month, all with diverse and intersecting needs.

As the pilot program continues into its third year, Health & Medicine Policy Research Group (program coordinator) and Sinai Urban Health Institute (lead evaluator) recently released the pilot’s Year 2 Outcomes report. The report summarizes the learnings and outcomes of the pilot during a significant and challenging 2020.

“The pandemic has shown in stark relief the value of trusted messengers within communities,” said Margie Schaps, Executive Director of Health & Medicine Policy Research Group, “Staying on top of information about the virus, public health strategies to address the virus, and vaccines have been so complex for everyone, and, in many communities, it is the CHW who is turned to for trusted, reliable information.”

Aging Care Connections, Alivio Medical Center, BEDS Plus, Healthcare Alternative Systems, and Mujeres Latinas en Acción are the five pilot organizations currently participating in the program. While each organization’s area of focus and population served may vary, the pandemic illuminated how interconnected community needs are and how inequities and lack of health infrastructure in the western suburbs work in tandem to influence health outcomes.

“For the first two months, we were getting so many calls,” said Ms. Moreno, “People wanted help from someone in their community who could understand the different barriers that come with being an immigrant or being someone who is currently going through domestic violence and being locked-down puts a lot on our mental health.”

How the CHW Pilot Was Started

In 2017, Community Memorial Foundation learned that residents felt disconnected from information about social services and resources during a community listening session commissioned by its Regional Health and Human Services Agenda’s Healthcare Access Action Team. Healthy Communities Foundation joined the effort in early 2018 and held several joint discussions and focus groups with community partners that sparked the idea of developing a community health worker workforce in the western suburbs. The CHW model would help address the gap in health education and lack of access to high-quality health and human services to west suburban residents.

“The western suburbs have experienced rapidly shifting demographics in the last ten years, and with that, clear health and racial disparities have emerged,” says Nanette Silva, Program Director at Community Memorial Foundation. “The CHW model promises equitable engagement at the grassroots level by cultivating trusted community representatives to become educators, advocates, and relationship builders.”

From the onset, the program team knew that collaboration between the pilot organizations would be critical to the CHW workforce and the community members they serve. The pilot was designed as a learning collaborative, uniting 12 CHWs from five community organizations serving diverse populations. Facilitated by Health & Medicine Policy Research Group, the CHW learning collaborative is the first of its kind in the country. It provides CHWs and their supervisors with ongoing education, support, and the ability to learn from one another while also acquiring skills and tools from experts in public health and social services. As it turns out, the collaborative proved to be invaluable to its organizations and respective communities when suddenly faced with the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The resources that we offered have changed. The needs have changed. We need to reinvent.”

At the end of Year 1, the program team formulated the Year 2 plan and was ready to implement it. Then, the pandemic hit and forced the program to shift and adapt to new circumstances.

“The CHWs had to reimagine new ways of connecting with communities, and, in a matter of days after the lock-down started, they began to respond to the pandemic by leveraging their skills and knowledge of existing community resources, and relationships they have built with partner organizations,” said Angela Eastlund, Workforce Policy Analyst & Schweitzer Program Associate at Health & Medicine Policy Research Group.

The pandemic highlighted unique challenges and creative adaptations as each organization rapidly shifted operations and adjusted workflows. With in-person gatherings no longer advisable, organizations quickly responded with an innovative range of virtual programming in addition to individual client meetings over the phone or through Zoom. The support they provided included everything from educational sessions to navigating telehealth appointments and hosting interactive webinars.

“The resources that we offered and had to look up have changed. The needs have changed. The outreach has changed. The way we work–taking intakes digitally and making sure I have my computer on me,” said Ms. Moreno. “We had this beautiful calendar of where we were gonna go out in the neighborhood and explore and go to different libraries and park districts. Now, we can’t do that. So, we need to reinvent.”

CHWs also saw increased demand for services in response to the “twin pandemics of systemic racism and COVID-19.”¹ The pandemic’s disproportionate effect on communities of color magnified the need for assistance in navigating complex health and human service systems and connecting clients to timely, necessary resources.

The increased need for services coupled with the use of virtual modalities significantly impacted Year 2 of the pilot.

Year 2 Outcomes

Year 2 Outcomes

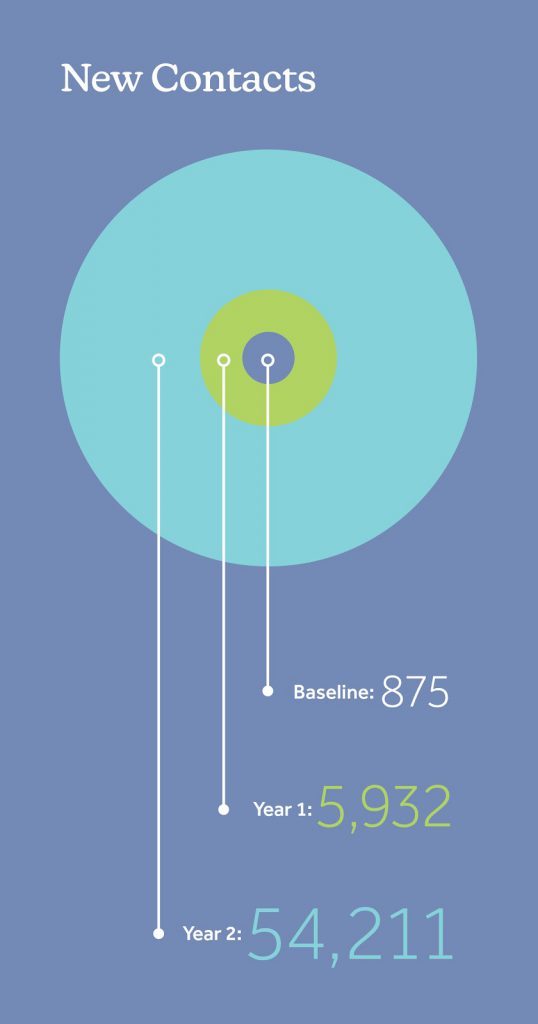

Technology Increased CHW Outreach to a Larger Audience

At the end of Year 2, CHWs across all organizations held 453 outreach events and engaged with 54,211 new contacts— a nearly tenfold increase from Year 1. This substantial increase was primarily due to wide-reaching virtual programming, such as free community webinars and live social media presentations that reach a significantly larger audience.

“The CHWs have identified that technology can be both a benefit and a barrier for the interpersonal nature of their work,” says Ms. Eastland. “While they still prefer and value one-on-one connections out in the community, the CHWs have found great success in the efficiencies and broad reach of virtual outreach methods.”

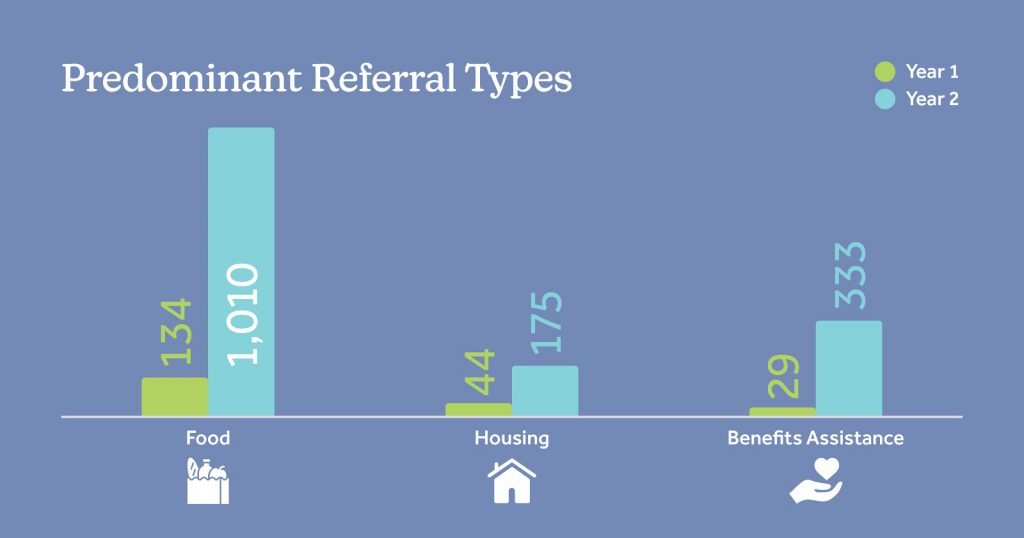

Predominant Referral Types Highlight the Pandemic’s Effect on Social Determinants of Health

Referrals for basic needs and benefits assistance surged in Year 2, as communities grappled with COVID-19 and its disproportionate effect on communities of color.

“Addressing social determinants of health such as food insecurity, housing assistance, access to transportation, and more has largely been the role of CHWs during the pandemic,” said Ms. Schaps, “These needs will continue as we climb out of this period and rebuild our communities.”

Web-based Platform Uses Technology to Manage Increased Need and Improve Closed-Loop Referrals

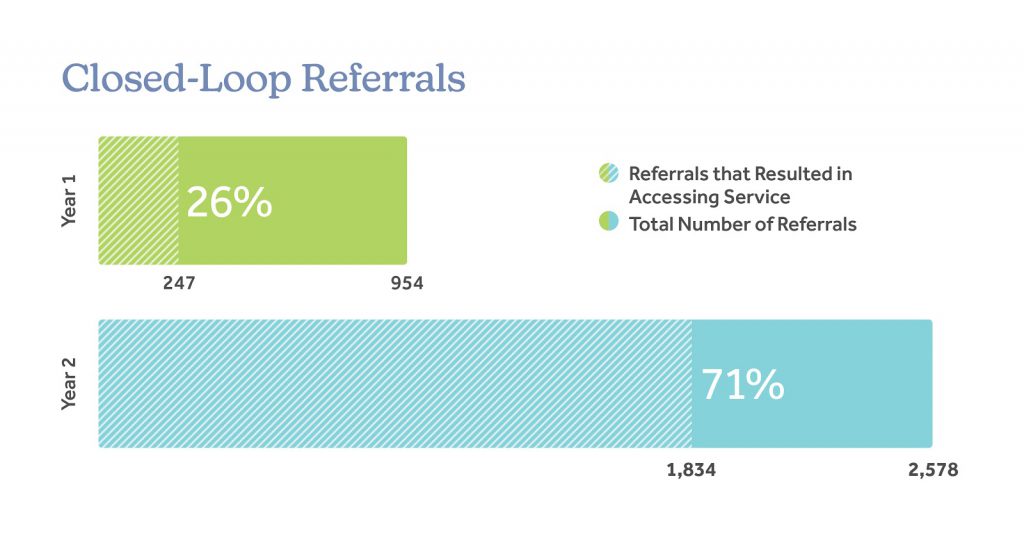

Referrals resulting in accessed services increased from 26% in Year 1 to 71% in Year 2 , largely due to The HUB.

In Year 1, CHW organizations could not readily determine the outcome of a referral due to the lack of an integrated system. In Year 2, they incorporated The HUB, a web platform designed for collaboration within community-based organizations, in their workflows. With this integration, organizations can easily search for social service support, connect directly with referral locations for a warm hand-off, and more easily track whether a client receives referred services.

Looking Ahead: “There is potential for this model to strengthen inter-organizational collaboration and create a more robust safety net.”

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, CHWs became organizational champions. Their flexibility and knowledge have solidified their role as trusted community messengers and accelerated the impact of their agencies during this challenging time. As the pilot evolves into Year 3, the collaborative believes that myriad public health and social service efforts can leverage the influential role of the CHWs in the years ahead.

“The pandemic has revealed not only the critical role that community health workers have in addressing health equity and building community trust, but the potential of this model for strengthening inter-organizational collaboration and creating a more robust safety net,” says Nora Garcia, Director of Programs at Healthy Communities Foundation, “As the pilot has evolved from its 2018 inception, the collaborative has been encouraged by the level of interest from organizations, workforce institutions, and government in understanding best practices and the value of lived experience within communities.”

In late March 2021, the Illinois House of Representatives passed House Bill 158, a health reform bill addressing certification and reimbursement for CHWs. This momentum is critical to engaging additional funding partners to grow the CHW network throughout the western suburbs of Chicago and advocate for the expansion and accreditation of a CHW workforce.

“A silver lining of the pandemic is that it has highlighted the benefits of CHWs in the public health workforce to a broader audience,” says Ms. Eastlund. “This will promote the expansion of their role throughout the State of Illinois and ultimately reduce disparities in health outcomes across all our communities.”

—

While the expanding CHW network promises change at the macro-level, the micro-level interactions between CHWS and their clients directly impact the health and wellness of our west suburban neighbors and create deep-rooted trust in the communities they serve. Throughout the past year in particular, CHWs like Jocelyn Moreno have provided connection, respite, and understanding.

“A lot of times, especially with our community, we’re very prideful and we don’t like for people to think, ‘Oh, you can’t sustain yourself,” says Ms. Moreno, “Or two, we’re scared that getting help can affect public charge, or clients think they might not qualify for any of the help. A lot of community members are like, ‘What’s out there for us? Who’s gonna help us?”

As CHWs mobilized throughout the pandemic, communities began to recognize them as knowledgeable, trusted, and embedded community partners who understand the different barriers that their clients are facing. Says Ms. Moreno, ”It was amazing to see what comfort they ended up getting with us.”

¹ Kolod, S. (2020, June 16). The twin pandemics of racism and covid-19. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psychoanalysis-unplugged/202006/the-twin-pandemics-racism-and-covid-19